Four architects and artists displaced during Nazi persecution

Holocaust Memorial Day encourages remembrance of the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust, alongside the millions of other people killed under Nazi persecution and in genocides that followed in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and Darfur.

Many architects were among those persecuted and displaced because of their faith, ethnicity, sexuality or way of life. Among them were a number of architects whose work can be found in our collections. This Holocaust Memorial Day we’re sharing the work of four architects and artists who were forced to flee their home countries to escape persecution, as we join those around the world in honouring Holocaust survivors and reflecting on the lives that were tragically cut short.

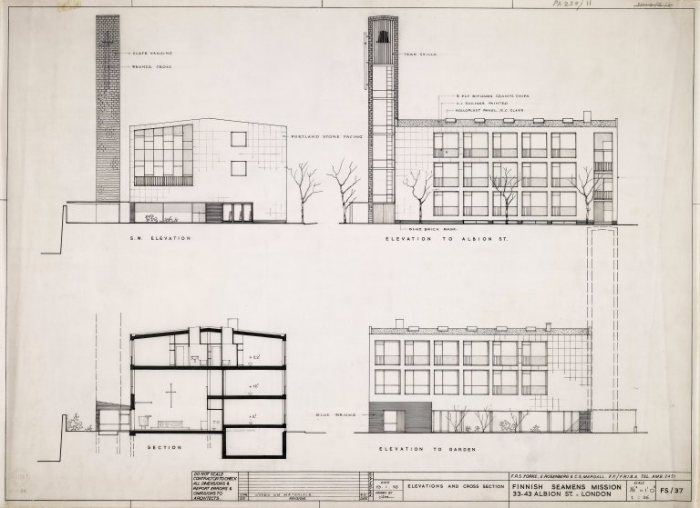

Eugene Rosenberg (1907-1990)

Eugene Rosenberg was born in Slovakia, but by the time he was 27 he had established his own practice in the Czechoslovakian capital, Prague. Among the practice’s projects was a shopping arcade alongside apartments and offices on Ve Smečkách in Prague’s city centre.

Rosenberg was still in Czechoslovakia when it was occupied by German forces in 1938, but escaped to Britain the following year. His ‘welcome’ in Britain was short-lived, however. In 1940 he was shipped to Australia, one of around 7,500 so-called enemy aliens who were interned in Australia and Canada.

Rosenberg returned to London in 1942, where he founded York Rosenberg Mardall (YRM) alongside F.R.S. Yorke and C.S. Mardall. The practice’s projects included schools, hospitals and civic buildings as part of large-scale post-war rebuilding efforts. This 1956 drawing shows YRM’s design for the Finnish Seamen’s Mission in Southwark, south London.

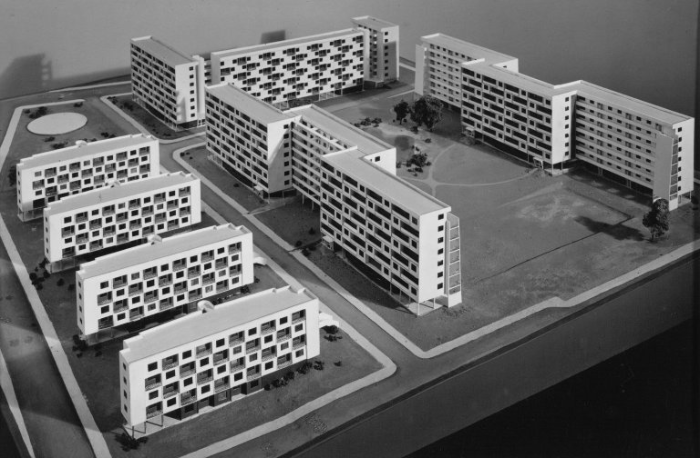

Carl Franck (1904-1985)

In 1937 the Reich Chamber of Visual Art wrote to Carl Franck, forbidding him to continue practising as an architect. Unable to earn a living and fearful for the safety of his Jewish wife and their family, Franck left Germany for England, where he hoped to secure a job and arrange passage for the rest of his family to follow.

By the start of 1938, Franck had managed to secure work with the architectural practice Tecton, and his wife and son were finally with him in London. Franck worked on the design of Tecton’s apartment buildings in Finsbury.

Like Rosenberg, Franck had to navigate the restrictions imposed upon refugees deemed ‘enemy aliens’, which prevented him from travelling more than five miles from his apartment, and meant that he couldn’t own street plans. When Poland was invaded in 1939, Franck was among refugees transported and interned on the Isle of Man. He remained there for six months until his release, after which Finsbury Council put him in charge of the design and construction of air raid shelters.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946)

Moholy-Nagy was a painter and photographer, who went on to work closely with, and teach alongside, architects of the Bauhaus school. He was born László Weisz, to a Jewish family in Hungary, but changed his name after his father left the family. Moholy-Nagy moved to Berlin in 1920, but when the Nazis came to power in 1933, he was no longer allowed to work in Germany, because he was a foreign citizen. He moved briefly to the Netherlands before settling in London in 1935, where he became part of the circle of émigré artists and architects based in the Isokon building, in north London. In 1937, he relocated to Chicago to head up the New Bauhaus school there.

In the same year, work by Moholy-Nagy was exhibited in the infamous Nazi exhibition titled 'Degenerate Art', which denigrated modern art and aimed to inflame public opinion.

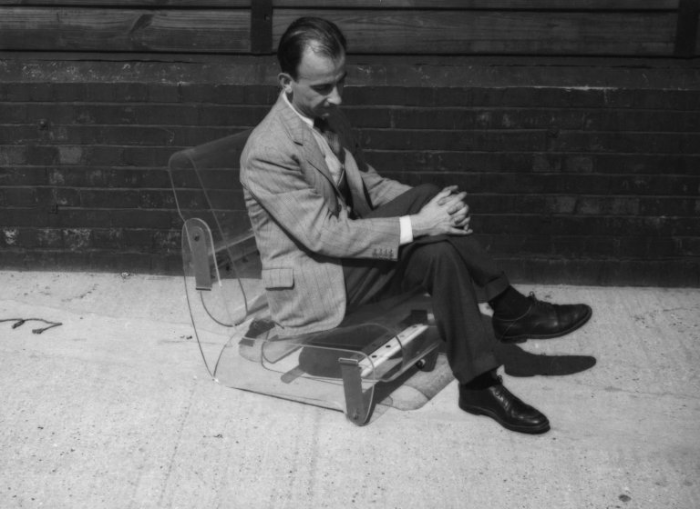

Peter Moro (1911-1998)

Peter Moro was forced to leave university in Berlin in 1933 when the Nazis discovered he had a Jewish grandmother. He went first to Switzerland and, after completing his studies in Zurich, arrived in London two years later.

After some difficulty initially finding a job, Moro eventually met Lindsey Drake, another member of Tecton, and began working with Berthold Lubetkin. Like Rosenberg and Franck, Moro also found himself treated as an enemy alien, and was briefly held on the Isle of Man.

Moro’s projects included an important private modernist house for a steel manufacturer called Harbour Meadow in Birdham, Sussex. After the war ended, he founded his own practice, Peter Moro and Partners, who were responsible for designing a school in Lewisham, south east London, as well as housing for the Greater London Council and later the Nottingham Playhouse.

Despite often being treated with hostility and suspicion as refugees in the UK, many architects like Rosenberg, Franck and Moro went on to be a major force in Britain’s post-war rebuilding efforts. Their buildings serve as a legacy of those who lived through Nazi persecution. They also remind us of the many others who did not survive the war, such as chief architect for Prague-based firm Emil Gerstel, Arthur Blitz (1903-1944).

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked *)

- Peter Moro oral history interview, British Library National Life Story collection*

- Julia Franck, ‘On The Track of Family History’*

- RIBA Refugee Committee Papers, via RIBA Collections

- RIBA Photographs Curator Valeria Carullo’s ongoing research into the RIBA Refugee Committee*

- Angeli Sachs, Edward van Voolen (ed.), ‘Jewish Identity in Contemporary Architecture (Munich and London: Prestel, 2004)

- Eran Neuman, ‘Shoah Presence: Architectural Representations of the Holocaust’ (Farnham: Ashgate, 20014)

- Images of Eugene Rosenberg’s work on RIBApix

- Images of Carl Franck’s work on RIBApix

- Images of Peter Moro’s work on RIBApix

- Images of László Moholy-Nagy's work on RIBApix

Updated: 27 January 2025 (originally published in January 2023)