New Delhi

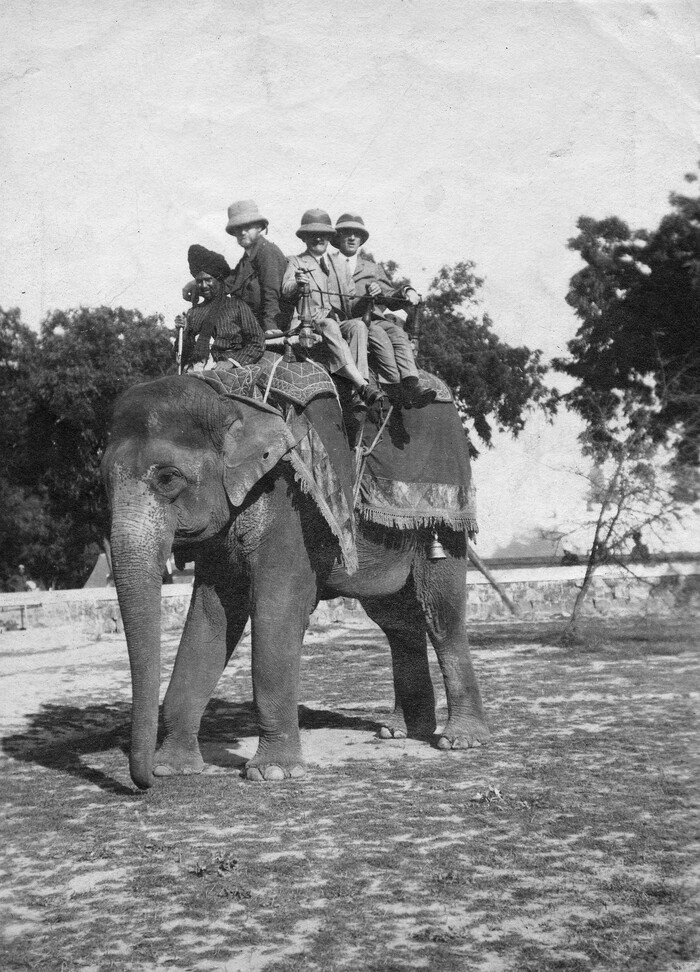

The year is 1912, and India is under the control of the British Raj.

King George V has recently announced the removal of the Indian capital from Calcutta (now Kolkata) to Delhi, and English architect Edwin Lutyens has been appointed to the commission responsible for the design of this new legislative centre: New Delhi. Its key building is the Palace (though always referred to as the House) of the Viceroy of India, the British Monarch’s representative in India.

Back in London, another architect, Herbert Baker, pens a letter to Lutyens setting out his own vision for New Delhi. He writes, “it must not be Indian, nor English, nor Roman, but it must be Imperial”.

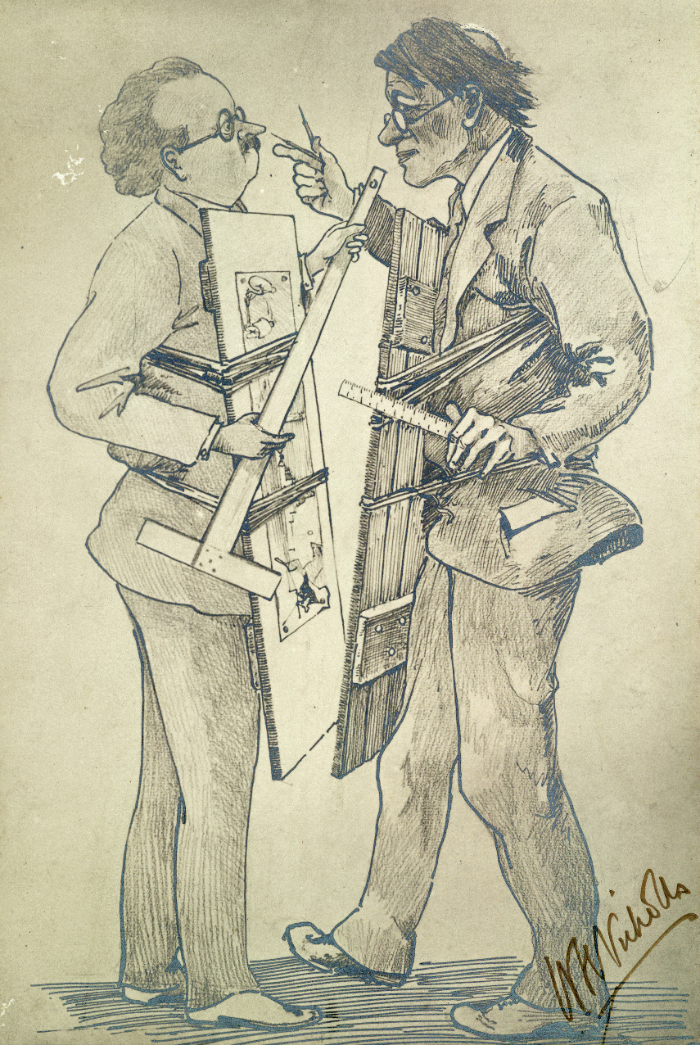

The statement illuminates a presumption of British cultural supremacy in the colonial era. Baker, who joined Lutyens in Delhi to design the Secretariat Buildings and Parliament House, wrote separately that India had no “real” architecture of its own, and was reliant on the West to import its “intellectual progress”. The two architects did not always agree; in fact, they went on to argue fiercely (see Image 6). But Baker’s statement reveals the context in which they worked, as architects for the British Raj, responsible for expressing its power and authority through its buildings. Baker later became a member of the RIBA Council, and when RIBA’s London headquarters building opened in 1934, the New Delhi structures – seen as symbols of the institute's empire-wide scope – were among the buildings immortalised on the sliding screen mural of the Jarvis lecture hall (Image 1).

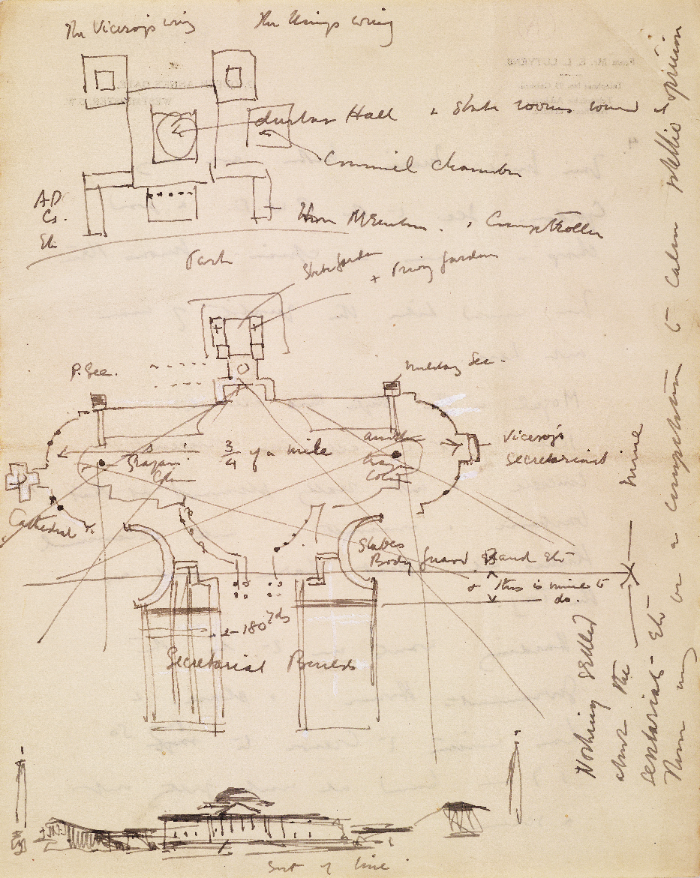

Lutyens and Baker were both prolific letter-writers, corresponding with contacts in Delhi and London, and most revealingly with their wives, as well as with each other. Hundreds of these letters (such as Image 5) are held in the RIBA Collections, offering a vital glimpse of the attitudes and considerations that underpinned the design and construction of New Delhi.

But what exactly did Baker mean by “imperial”?

The Viceroy’s House was a highly visible physical expression of Britain’s power in India. It was vast in scale, sitting at the heart of an even larger urban complex. This scale was important, forming a significant part of negotiations between Lutyens, Baker, and the Viceroy, Lord Hardinge. Hardinge had envisaged that the Viceroy’s House should be seen from every part of Delhi, and Baker argued his Secretariat Buildings should share this prominent position, creating an architectural expression of unity between the Viceroy and his government.

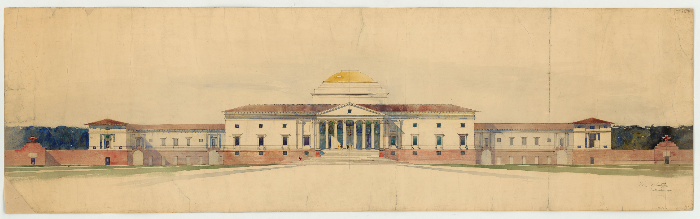

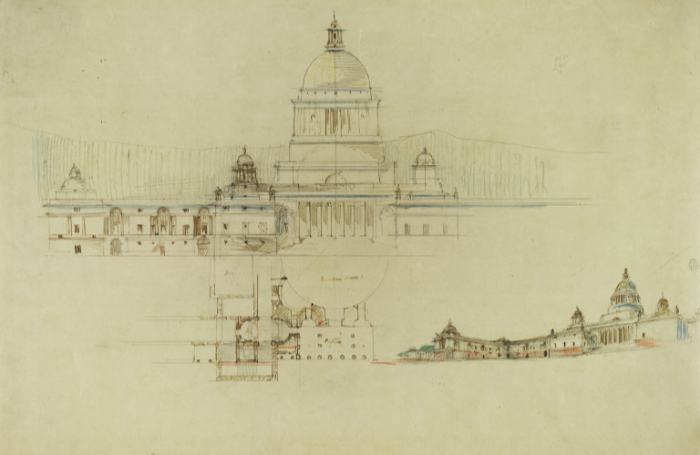

Lutyens’ early ideas for the Viceroy’s House were varied. One idea (Image 2) was an immense Palladian country house, combining a shallow dome with the expansive portico and spreading wings of Andrea Palladio’s villa Mocenigo. Another scheme (Image 4) took inspiration from Sir Christopher Wren’s St Paul’s Cathedral in London, and the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich.

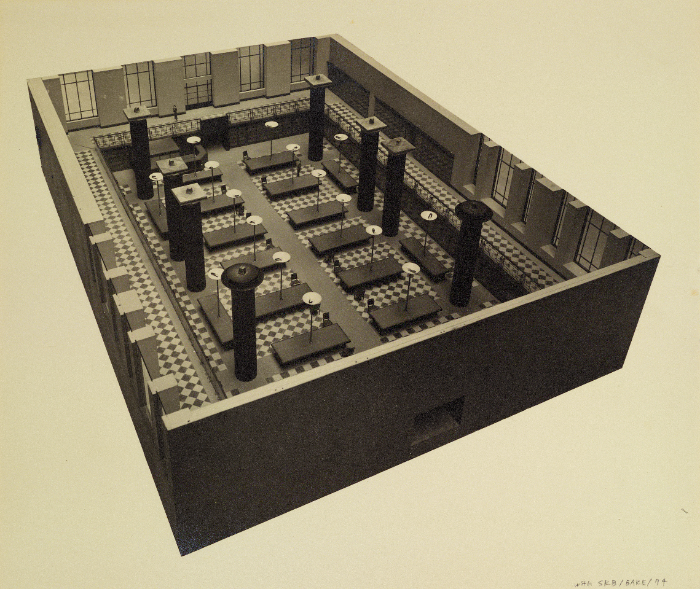

At the heart of all of the proposals was the classical architecture of ancient Rome, aiming to represent a sense of the ordered rationalism that the British administration credited itself with introducing to its rule of India. Under pressure to represent a sense of joint British-Indian government, both architects developed hybrid styles, combining what they considered the “nobler” features of Mughal, Buddhist, and Hindu architectural traditions with Western traditions. For example, the models of the Pantheon and Wren that Lutyens had considered for the dome over the ‘Durbar Hall’ were succeeded by an adaptation of a Buddhist stupa and both architects replaced classical cornices with the deep, shading chujjas characteristic of many Indian forts and temples. However, the hybrid nature of the exterior forms was not generally replicated inside and the prevailing style was neo-Georgian, which emphasised the ‘Britishness’ of the architecture. Both architects had only limited interest in the architecture they found in India, which Lutyens had dismissed as “all pattern”.

Of course, Baker and Lutyens were far from the only figures involved in the design and construction of New Delhi. The project called for a local team of Indian architects and craftspeople. In fact, Baker later reflected that New Delhi was, but for a few exceptions, “executed entirely by Indian workmen”. Among them was Narain Singh, who rose to prominence building the foundations for the Viceroy’s House, as well as many of Delhi’s new roads.

There were also aspirations to employ local craftspeople, wherever possible, to produce the furniture and decoration at the Viceroy’s House and murals and carved jaalis (screens) for Baker’s Secretariats. In doing so, the British administration believed their own "expert supervision” and patronage would succeed in "reviving” Indian crafts to a higher standard. An unrealised scheme for the Durbar Hall (the central chamber beneath the dome of the Viceroy’s House) would have seen its domed ceiling decorated with a painted frieze detailing India’s history, adapted from indigenous works of art. It was scrapped, in part because Lutyens (presumably missing the irony) claimed there were no sufficiently talented painters in India. Nevertheless, under the supervision of Percy Brown (curator of the Victoria Memorial Hall in Kolkata) and Munshi Ghulam Husain (Vice-Principal of the Government School of Art in Lucknow) a team of Indian artists adorned the building’s Council Room with painted map murals. Perhaps tellingly, the maps were based on those produced by European cartographers in the 16th and 17th centuries, against the backdrop of European colonial expansion.

Lutyens and Baker’s attitudes about the superiority of Western architecture, although more widespread during the time of the British Empire, were not universal. In 1924 while the Viceroy’s House was still under construction, Henry Vaughan Lanchester (British architect and editor of The Builder) argued in an article for The Architectural Review that the richness and diversity of architecture in India tended to be overlooked by British architects because of a lack of Western familiarity with it. He pointed out that “India is represented at Wembley by a group of buildings which the Indian artist would disclaim as in no way characteristic of his art”.

The architectural press in India illuminates how attitudes towards New Delhi varied based on whether you asked a beneficiary or victim of colonialism. Writing in the journal of the Indian Institute of Architects in 1935, Claude Batley (an English architect who migrated to India in 1913) claimed the new capital had been “undoubtedly the greatest opportunity for righting the wrongs that Indian architecture had suffered from the time of Aurangzeeb onwards; India then was, however, entirely unprepared to grasp it...”. By contrast, the Indian journalist Inder Malhotra pointed out in the same journal in 1977 that Delhi’s colonial housing had been “put up and maintained at great cost to the poor tax-payer for the benefit of rulers, past and present”.

The exploitation of local workers employed in the construction of New Delhi, and the harm caused by the British colonial project for which the city was a symbol, are now more widely recognised and understood. In 1950, the Viceroy’s House was renamed Rashtrapati Bhavan (‘President’s House’) and is the official residence of the President of India.

Find out more about symbols of the British Empire in RIBA's buildings and collections.

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*)

- G.A. Bremner (ed.), ‘Architecture and Urbanism in the British Empire’ (Oxford University Press, 2016)

- Andrew Hopkins and Gavin Stamp (ed.), ‘Lutyens Abroad’ (London: The British School at Rome, 2002)

- Robert Grant Irving, ‘Indian Summer: Lutyens, Baker, and Imperial Delhi’ (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981)

- H.V. Lanchester, ‘The Architecture of the Empire’ in Architectural Review (June 1924)

- Clayre Percy and Jane Ridley (ed.), ‘The Letters of Edwin Lutyens to his Wife Lady Emily’ (London: Collins, 1985)

- John Stewart, ‘Sir Herbert Baker: Architect to the British Empire’ (North Carolina: McFarland, 2021)